18/05/2021

Transformation, News, Insights

Is the future of care treating more people in their own beds at home?

Jessica Solomon from our Transformation Team explains how Urgent Community Response Standards and ‘out of hospital’ care could be better for both the individual and the NHS.

Life expectancy in the UK has increased from 68 to 82 since the NHS was founded in 1948 thanks to advances in public health and medical care. And it’s set to increase further with the proportion of over 85s in the UK predicted to more than triple by 2066 according to the ONS.

This great progress brings its challenges, with more people than ever before living with multiple long-term medical conditions and complex social care needs. To address this, the NHS long term plan shifts to ‘out-of-hospital’ care and introduces the Ageing Well programme, which focuses on improving quality of life.

One of the pillars of this programme is the introduction of two Urgent Community Response Standards which systems nationwide are expected to achieve in the next 3 years to reduce unnecessary admission and stays in hospitals.

In this article, we’ll tackle how reaching these standards would lead to better care, and deep dive into methods that need to be employed in the NHS to achieve these standards.

But first, what are the standards?

The first is a two-hour standard for crisis response care. Within two hours of a referral, a health or social care professional visits a person at their home to provide them with intensive support, aiming to prevent hospital admission.

The second, is a two-day standard for reablement care. Within two days of referral the person is assessed, and a tailored package of support put in place. This could involve multiple health professionals such as physiotherapists and Occupational Therapists, but with an emphasis on social care support.

Avoiding admission is better for the individual and better for the NHS

From my experience as a doctor, the vast majority of people would prefer to stay at home, in their own bed rather than being admitted to hospital, if at all possible. This is also the safer option as at home the risk of catching a hospital-acquired infection or COVID is reduced.

For the patient this is better as multidisciplinary care at home can maintain independence and prevent the deconditioning associated with bed rest in hospital. Meanwhile remaining in familiar surroundings means falls are less likely and the risk of developing delirium (acute confusion), which can occur in around 20% of older people admitted to hospital is lower.

Care at home can also help to relieve pressure on hospitals at several points too – driving cost savings that can be reinvested into improving services. Fewer patients requiring an ambulance and presenting to the emergency department means faster emergency care to those with the greatest medical need. Avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions will make acute beds available more quickly for those who need them.

How can we deliver these standards successfully?

Integrated services

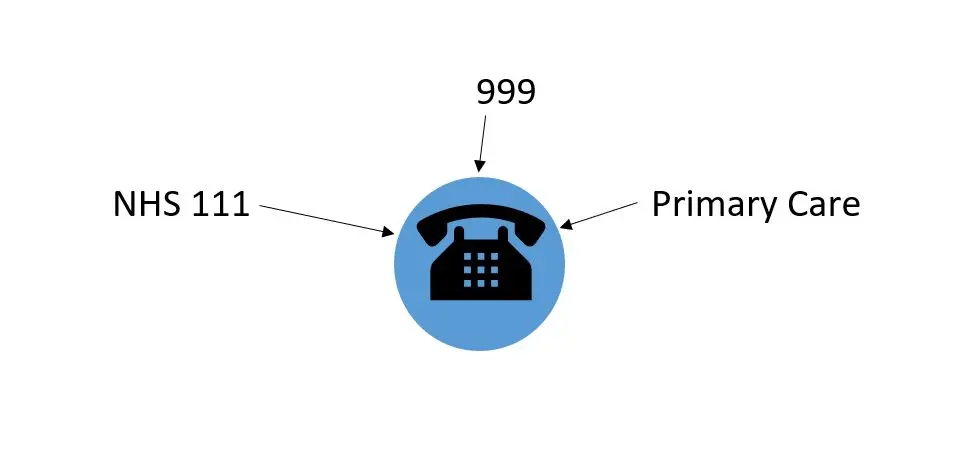

Referral pathways need to be integrated with key services such as 111, 999 and primary care. For this to happen successfully the Directory of Services must be updated in each area to include these services. This is particularly important with the roll out of 111 First, which asks patients with urgent or non-emergency issues to call 111 prior to attending the emergency department. As the use of this pathway increases, there is an opportunity to triage patients to the most suitable services, avoiding unnecessary admissions.

Good integration with 111 First would involve a patient who is experiencing an acute problem such as a deterioration of a pre-existing mental health condition, calling NHS 111 and being triaged to speak with a 111 clinician. The clinician should have knowledge of the services available or could use the Directory of Services, and if appropriate would be able to refer the patient for crisis response care, via a single point of access such as a phone number. For patient safety the referral process should involve a telephone discussion with the referring clinician.

High quality and safe responses

There should be clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that only patients who are safe to remain at home are triaged for these services. Referrers should be aware that the urgent care standards to do not replace existing services such as the Emergency Department, and patients with emergency needs such as injuries from a fall should continue to access emergency care in the same way.

If, once the patient has been reviewed at home the clinician feels they need to go to hospital, there should be simple pathways via a single point of access to refer them in. As we discussed towards the beginning of the year in our SDEC roundtable, this could involve direct links from the community services to an on-call specialist consultant for advice, or into a frailty SDEC for a comprehensive assessment.

Sufficient capacity

In order to provide the best care whatever day of the week someone becomes unwell, services should be available seven days a week, and designed to cope with local patterns of demand. The ability to do this is dependent on employing sufficient skilled staff to run these services. The recruitment and retention of healthcare professionals such as OTs, physios, nurses and social care practitioners is key to ensure that there can be ongoing high-quality input from multi-skilled and multi-disciplinary teams in the community. Successfully collaborating with primary care networks and their aligned expanded community teams will also be essential to the success of these services.

These standards in isolation will not be the answer to improving care for patients and delivering more care in the community. Experts are warning that it will not be possible to meet either target without a significant increase in the number of staff available. There are currently staffing shortages in many community roles, including district nursing where numbers have fallen by 40% since 2010. Implementation of these standards will require ongoing investment, and a focus on the training and recruitment of staff to make a lasting difference.

All of the elements required to successfully implement these standards rely on working within a joined up and integrated system, both at a local and at an integrated care system level. With the final areas of the country becoming integrated care systems this month, and the expanded powers that these changes afford them, we need to seize this opportunity to make integrated care in the community work.

Author: Jessica Solomon

Latest News & Insights.

The PSC is committing to new, more challenging sustainability targets

We are delighted to announce that we are committing to new, ambitious emission…

What does a good net zero programme look like for Integrated Care Systems?

The NHS has committed to reaching net zero in 2045 and Integrated Care Systems…

The PSC Wins Double Silver at the HSJ Partnership Awards 2024

We are delighted to announce that we have been awarded double silver at The HSJ…