Higher Education: immediate COVID-19 response and recovery

Higher Education institutions have been at the forefront of the immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but how can they ensure sustainability in the long-term?

COVID-19 has presented a number of unprecedented and immediate challenges for Higher Education, which have been effectively managed by the vast majority of providers. This has included not least the wholescale delivery of teaching through digital platforms, but also the spearheading of research efforts into tackling the pandemic. However, in the longer-term, providers will need to be focused on their ‘recovery’ phase and, alongside the government, the sector may need to make some complex and difficult decisions, particularly around financial sustainability and student retention.

Immediate response

The Government announced the physical closure of all school and college buildings from Monday 23rd March with exceptions for key workers’ children and vulnerable individuals. All Higher Education providers have similarly suspended face-to-face teaching, and many have completely closed campuses which has ushered in an unprecedented era for education. Immediate and significant changes taking place include.

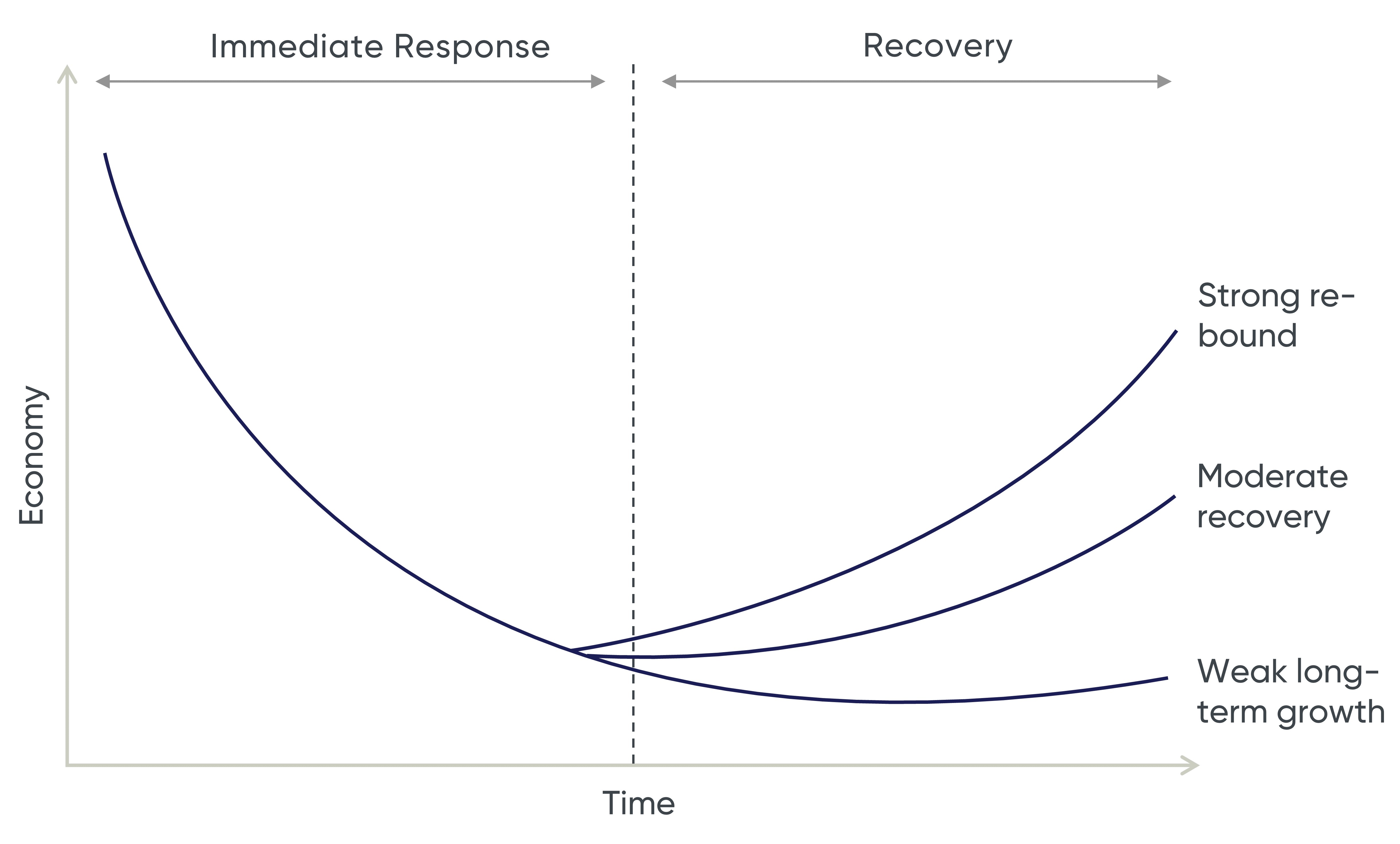

Figure 1: Illustrative economic impact of COVID-19

Rapidly implementing remote learning solutions that work

- Ensuring that students still have access to course content to complete their studies. Providers are using a range of platforms such as Blackboard, Moodle and Minerva

- Supporting lecturers to have the skills and capabilities to deliver remote teaching. For example, Sheffield Hallam University Digital Learning Team are offering a range of online staff development sessions

- Ensuring that remote learning solutions are accessible for all students, such as those with special educational needs or those without access to technological infrastructure at home

Maintaining financial solvency

- Maintaining financial solvency and cash reserves following the loss of multiple streams of revenue

- Influencing the government to support the sector with necessary policies and a financial recovery package to ensure sustainability for institutions

Spearheading research efforts

- Supporting pandemic research, including with the COVID-19 Genomics UK consortium which currently includes 13 Higher Education institutions to act as sequencing centres for samples from confirmed cases

- Supporting the governmental response to COVID-19 through donations of equipment. For example, the University of Nottingham provided Thermo Fisher 7500 PCR machines to the government which can perform an estimated 20,000 tests a day

Delivering remote assessments

- Designing new methods of assessment that are fair, effective and immediately implementable for all students, particularly for practical assessments and apprenticeships. Leeds has laid out their policy on their coronavirus website

Supporting student welfare

- Supporting students where there is a duty of care, for example, in HE residences, and providing clear information, advice and guidance for financial support available to other students. For example, De Montfort University has established a hardship fund for students affected by COVID-19

- Providing pastoral support and safeguarding for vulnerable students

Recovery

Beyond the immediate response focused on research, finances, current students and mental health and wellbeing, Higher Education providers will face a prolonged period of recovery that is expected to dramatically alter the face of the sector.

Financial solvency

Before the COVID-19 crisis, a number of institutions already faced precarious financial positions: In the initial OfS provider registration process, 74 had formal communication over finances and 71 were subject to enhanced monitoring. The average net liquidity days for providers at the end of year 2 across the sector was 138 days.[1] Although OfS deemed this to be ‘healthy’, this buffer is normally expected to protect against financial challenges such as delays in collecting cash receipts and is, therefore, anticipated to be insufficient to protect against the current unprecedented financial pressures.

Providers will suffer losses from multiple revenue streams in the short and long term, including student rent, international student fees, catering, events and auxiliary services. This could be particularly problematic for the historically secure and prestigious research-focused universities whose business model of cross-subsidising research costs with overseas student income could be jeopardised.

Therefore, providers will likely be required to take difficult decisions on potential cost-cutting measures, even with likely government support and a relaxing of regulatory requirements. Services such as careers, counselling and student unions may be vulnerable. Measures may be considered such as increasing class sizes, reduction in courses or module choices, or expansion of courses that are cheaper to deliver, such as the arts.

On 26 March OfS announced changes to the reporting regulations involving the definition of ‘Reportable Events’, removing the obligations on providers to report on certain issues, including: the provider becoming aware of legal action, new partnerships, or temporary campus closures. Although this removes some of the regulatory burden in the short-term, liquidity dropping below 30 days and the cessation or suspension of the delivery of Higher Education have been designated new reportable events and are likely to be faced by some providers. Without a public shift in bailout policy, OfS deregistration of some providers appears likely, as does significant difficulty for providers in ‘full compliance’ once this temporary period ends.[2]

Student numbers

Following global restrictions on free movement that are expected to last for several months, international student numbers are anticipated to rapidly fall for September 2020 admission. Initially, this was anticipated to largely affect universities with significant populations of Chinese students, such as University College London and the University of Manchester. However, as the global crisis has spread, this has become a problem for all international student cohorts and will remain challenging even as travel restrictions are gradually lifted.

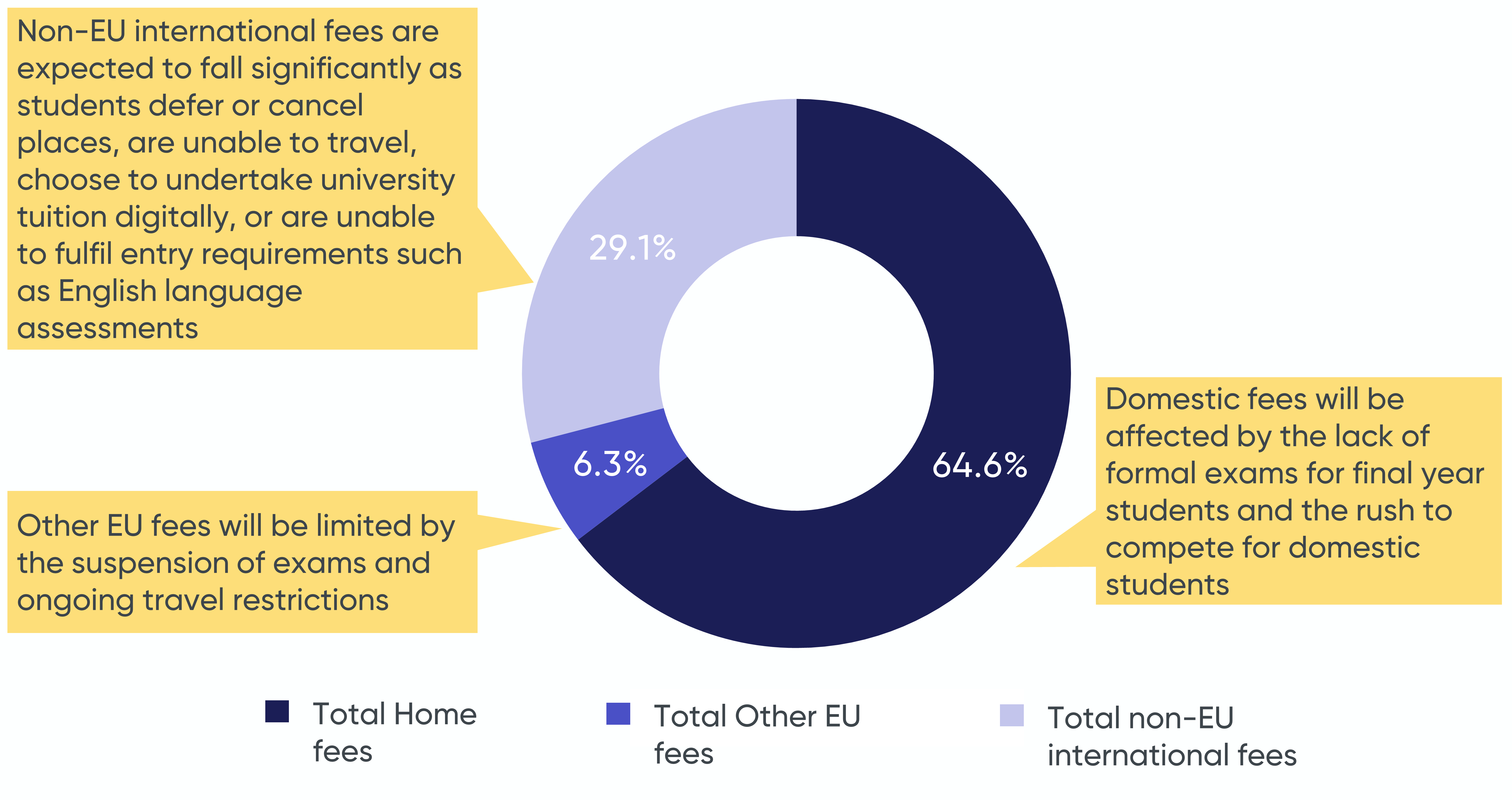

In 2017/18, tuition fee income from non-EU students represented 29% of total tuition fee income for Higher Education institutions, with the proportion much larger for Russell Group members.[3]

Figure 2: Tuition fee income sources 2017/18 (£'000s)

Aside from this anticipated collapse of international student numbers for September 2020, there also remains uncertainty surrounding incoming domestic students given the cancellation of exams and inability of students to visit providers.

This is expected to lead to a scramble for home undergraduates for September 2020, as already seen with the flood of HE providers making unconditional offers upon the Government announcement of a nationwide cancellation of exams.[4] Globally, there is mounting anticipation that caps on university places may be removed in countries such as Australia.[5] However, with already unrestricted numbers in the UK, HE institutions will need to carefully balance any increase in domestic student numbers with the quality of teaching for students and maintenance of institutional reputation. Certain leaders have already called for a suspension in the market for admissions and a re-imposition of student numbers controls through individual institutional limits to ensure that all institutions have viable first year populations.[6] It looks likely that the government will move towards this policy position which would be more beneficial for institutions having experienced recent rapid growth in domestic undergraduate numbers and more detrimental to those hoping to fill international places with more domestic students.

Student satisfaction

The effects of COVID-19 round off a tumultuous year for students following closely on the tail of UCU strikes earlier this year. HE institutions will have to carefully consider how to balance financial solvency with not just student numbers, but student retention, institutional reputation, and the moral and ethical responsibilities they owe to their students.

As the widespread campaigns for tuition fee refunds already demonstrate, few students are willing or expecting to pay up to £9,250 for half a year’s teaching and access to university facilities followed by no exams.

Competition is only beneficial to students if it drives up quality and the rush for home undergraduate revenue may lead to falling standards for students in the form of larger class sizes and reduced contact hours if sector-wide actions are not taken and government support not forthcoming.

Digital first

The necessary adaptations that are occurring in teaching methods and delivery present an opportunity to engage in pedagogical design to transform educational practices in the medium to long term. Digital platforms could enhance HE offerings through making the traditional lecture format more interactive, supporting a wider range of student needs, and employing the latest technology.[7]

For example, The University of Wolverhampton uses 3D visualisations to support more traditional lab-based sessions on anatomy and dissection.[8] Not only does the COVID-19 pandemic provide an opportunity to permanently redesign delivery of courses, but by the next academic year, students will expect that digital solutions have been thoughtfully designed for effectiveness rather than being hastily developed for necessity.

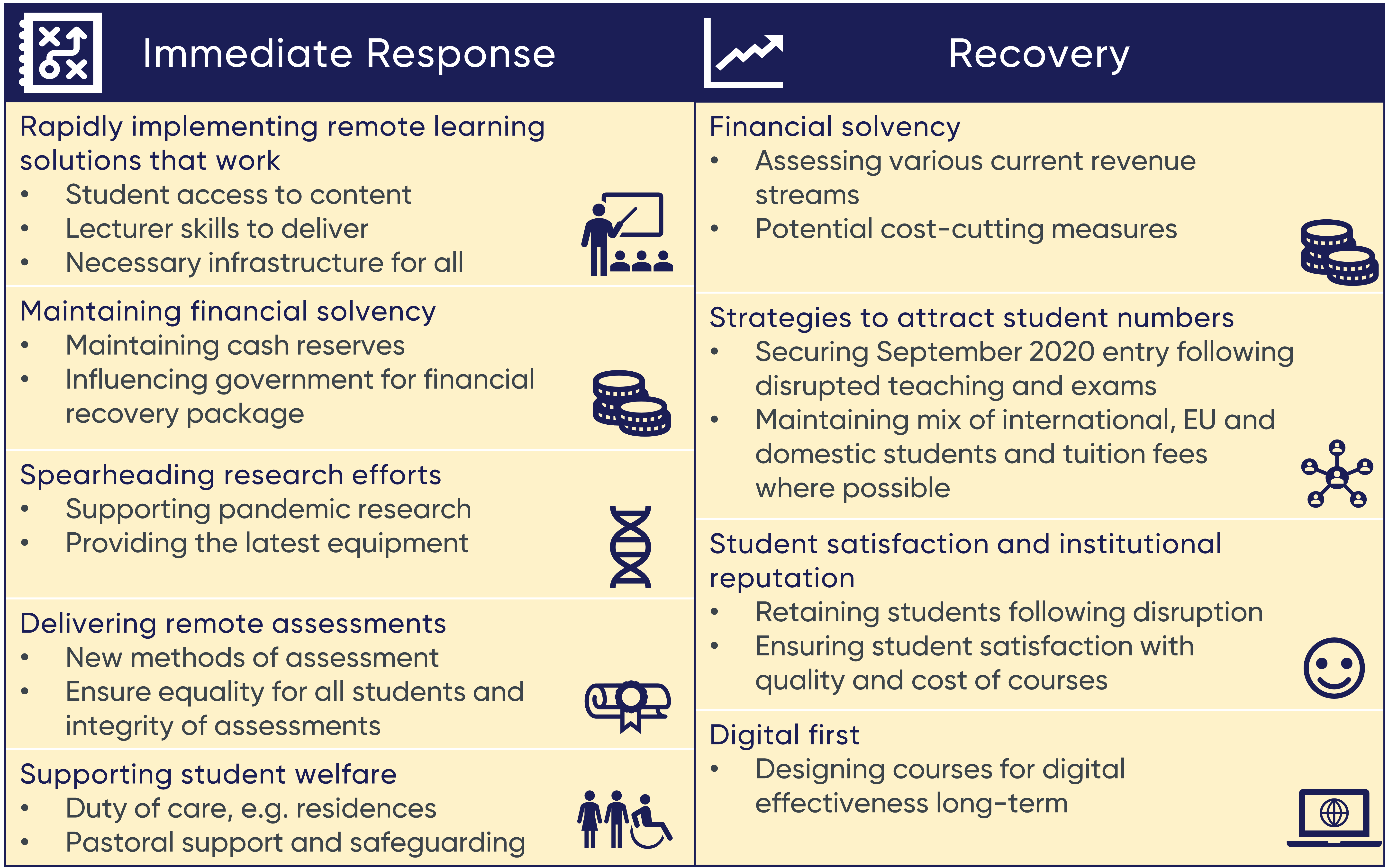

Figure 3: Summary of immediate response and recovery actions

Figure 3: Summary of immediate response and recovery actions

Summary

Faced with such an unprecedented challenge, HE providers have been at the forefront of the immediate reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic, not just for their students and staff, but for society at large. Unfortunately, the impact upon the sector will not be short-lived, and leaders need to consider how to face financial and operational implications, not just as individual institutions, but as a sector. Higher Education will be a key component of the future economic and social recovery and, therefore, requires government support and leaders committed to collaboration.

To find out more about our Education offer and how we might be able to help you, please get in touch with Antonio Weiss, Director at The PSC.

Authors: Ellie Lane and Antonio Weiss

References

[1] Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England, OfS, April 2019

[2] Regulatory requirements during the coronavirus (COVID-19 pandemic, OfS, 26 March 2020

[3] Raw data here and in charts obtained from the Higher Education Statistics Agency

[4] ‘Unis must stop unconditional offers in virus confusion’, BBC, 23 March 2020

[7] ‘Lecturing into your laptop is not nearly enough’, Times Higher Education, 24 March 2020

[8] Realising the potential of technology in education, Department for Education, 2019

Latest News & Insights.

The PSC is committing to new, more challenging sustainability targets

We are delighted to announce that we are committing to new, ambitious emission…

What does a good net zero programme look like for Integrated Care Systems?

The NHS has committed to reaching net zero in 2045 and Integrated Care Systems…

The PSC Wins Double Silver at the HSJ Partnership Awards 2024

We are delighted to announce that we have been awarded double silver at The HSJ…